Cool Choices

Since 2010, Cool Choices has inspired employees to embrace sustainability through an innovative game model. Organizations in sectors as diverse as commercial construction, health care, manufacturing, U.S. primary and secondary schools, and law have had game participants save hundreds of thousands of dollars and avoid tons of pollution annually because of sustainable choices made in Cool Choices games. Post-game independent evaluations have found statistically significant savings in energy (median electrical household savings of 6%) as well as savings in water usage - with the vast majority of sustainable practices continuing a year later.

Background

Note: To minimize site maintenance costs, all Tools of Change case studies are written in the past tense, even if they are ongoing programs, as is the case with this one.

Getting Informed

Informed by ongoing literature reviews, professional conference participation, outside academic experts and analysis of best practices from other behavior change programs, Cool Choices met with interested organizations, learned about their local culture and identified opinion leaders for “Action Teams” to help inspire and direct games. Baseline surveys and, on occasion, limited (four week) demonstration games further informed Cool Choices’ audience engagement efforts prior to starting full games.

Delivering the Program

The game successfully inspired individuals to take sustainable actions and record them by making the process fun, social and easy.

Serious Fun

Cool Choices game cards offered simple sustainable practices that changed daily occurrences into fun, noticeable and rewarding opportunities. As participants took actions they “played” cards on a website, earning points for themselves and their team. The dynamics of cards, points, competition at the individual and team level, and leaderboards signaled that this was a game - and helped create a fun, new way for co-workers to interact with each other.

The game also rewarded players with prizes and recognition both randomly and for superior achievement. The prizes provided

- Ongoing incentives to play the game

- Encouragement for broad engagement of all players, including those “not in the lead” who could still win prizes; and

- A mark of prestige for players, although the prizes often had little or modest material value.

Very Social

The game was transparent to all players. As a way of promoting open, accountable and sustainable values, the game let everyone see their reported actions and points, the actions and points of other players, and team standings. The transparency served multiple purposes including:

- Keeping players ‘honest’ because they knew others could check up on them;

- Increasing the likelihood that new habits would persist because players wanted to seem consistent to their peers; and

- Reinforcing that a player’s co-workers were also taking action, giving all players a sense that sustainable actions were the “new normal” – a social norm - in their company.

Pictures Helped Tell the Story

Players got points for sharing pictures and stories of individual and family sustainable actions at home and in the community - like line drying laundry at home or bicycling to work to save energy. Sharing these pictures in the game blog made sustainability personal and real for many players, generating “water cooler” buzz about the game, increasing norm appeal and word of mouth promotion, helping visually connect co-workers to each other’s families and the broader community, and encouraging increased participation from everyone.

Competition Increased Engagement

A leaderboard provided team scores and standings, promoting team solidarity, friendly competition and plenty of reason to talk with co-workers about game developments. Team play reinforced the sense that sustainability was a shared value among team members and within the company. The competition among teams increased player engagement, turning individual sustainability commitments into team obligations where bonds of friendship, and peer pressure, strengthened sustainable practices.

Doing it Was Easy

The game design gave points to players for sustainable actions that were on cards and that they already did (e.g. carpooling or recycling items) - and new sustainable activities prompted by cards (e.g. replacing incandescent lights or exploring water use in their home). Recognizing actions players already did got player “buy-in” – and showed the player community that some sustainable actions were “easy” because people they knew did them.

Highlighting existing sustainable behavior also increased norm appeal as sustainability became more visible to the community and players became more likely to adopt the actions of their peers.

Players readily recognized and understood the cards, points and team format as well as the intuitive, simple website interface. Daily email reminders prompted action while card/actions with varying degrees of difficulty offered numerous opportunities for success. Many activities like eating local food, avoiding “jack rabbit” driving, or removing weight from the trunk of your car represented modest variations of common activities that still had sizable sustainable impact in the aggregate.

The game kept “results” easy too. The units of measurement were actions and points - and the game described total impact to players as: the number of players, the number of “Cool Choices” actions and the amount of money saved. Avoiding terminology like “kWh” and “therms” made the game easy, “relevant” and understandable for everyone. (Note that one Tools of Change peer reviewer said "The decision to avoid terminology like “kWh” overlooks and misses out on an important educational element. I see this as a bit of a missed opportunity. It’s important for homeowners to understand not only the types of energy-consuming activities in their lives but also the impact that each of these activities has in relation to annual household energy consumption. Improving “energy literacy” means making sure that homeowners/participants understand the basic units of energy, such as a kWh of electricity, a m3 of natural gas, etc.)"

Serious, Substantial, and Sustainable Action

While the game was fun, social and easy, the design was serious, substantial and sustainability-oriented. Cool Choices:

- Contracted with professional game development firms to take full advantage of the opportunities gamification offered;

- Collaborated with organization Action Teams to refine the game model so that it was consistent with the local culture and customized some game card sustainability activities to meet organizational sustainability needs or priorities. It also addressed barriers to specific actions as identified in the baseline survey, demonstration games, and in discussions with the Action Team;

- Worked with independent energy efficiency experts to identify environmentally sustainable actions and to quantify their benefits—in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, water, energy, and dollars saved; and

- Evaluated results formally with independent energy efficiency experts obtaining actual player household energy consumption from utility data, constructing surveys, conducting player interviews and evaluating programs.

Overcoming Barriers

The gamification strategy overcame some of the broader challenges relative to motivating and tracking consumer action on emission reductions.

Specifically:

- Individuals assumed climate change was not local. The game made actions local because it is played within the corporate community with an emphasis on local benefits.

- Climate change is gradual and slow, so it was difficult for an individual to feel they were making a difference. The game statistics changed weekly and changes were presented in their aggregate for greater impact/sense of progress.

- Emission reduction outcomes were not visible to those making changes. Points earned and an individual’s status in the game could be seen on the leaderboard for players to follow. Players got bonus points for sharing stories and photographs resulting in vivid stories of change.

- Negative effects of emissions seem far in the future. The game’s focus was on activities and benefits "now" versus negative impacts in the future; players reported, for example, numerous lifestyle benefits associated with actions that – for example - encouraged them to watch less television and drive less aggressively.

- Individuals felt that they could not make a difference. The game reinforced how small actions add up across players and teams

- Individuals believed that they had already done their part. Players got credit for actions they had already taken – but became aware of other actions people around them took. To succeed they needed to do new things.

- Messages about what to do were confusing; people were not sure what to do - or doubted they could do anything. Points were associated with specific, clear actions. Cards identified lots of potential actions – offering multiple options for success.

- Individuals believed that others were not doing their share. The game’s transparency, website of photos and stories, and players’ shared experiences illustrated that others were doing their part and provided motivation. The spirit of competition transformed people’s attitudes from, “I have done my part” to “I need to do more to win.”

- Self-reporting of consumer emission reduction actions suffers from inaccuracy on the one hand (due to poor memories or inflating results to “look good”) or lack of granular understanding of individual actions/practices on the other (comparing only utility bills.) The website instituted a same-day “playing” of cards system to get points (you could not go back to a prior day for credit), providing a daily record of actions; independent evaluations (including a baseline survey, player utility bill analysis, and player interviews) providing context and verification of results. [Note: In the initial pilot game with Miron Construction reporting was permitted weekly.]

It is important to note that some individuals had insurmountable barriers relative to some actions. Long-distance commuters could not walk or bike to work; renters could not change water heater settings, etc. The game, though, provided participants with multiple opportunities to make changes so that if one change did not apply, there were others that did apply. No one could say that the game wasn’t applicable to them.

Measuring Achievements

To earn points in the game, players had to report their actions daily in a transparent environment that discouraged exaggeration (this was done weekly in our initial pilot game with Miron Construction). Cards described specific actions and the savings assumptions associated with each card were verified by an independent third party. The savings assumptions were further altered and refined through post-game interviews from initial games that clarified ambiguities; for example, unplugged and recycled second refrigerators were often of a smaller-than-expected size.

Evaluations from independent energy efficiency experts included a baseline survey, analysis of reported action data, utility bill analysis, and post-game interviews with players to verify results reported. Additionally, an independent evaluation follow-up has measured persistence of sustainable habits one year later. While there was no control group to verify impacts from the game versus other influences, pre- and post-game surveys have included employees not involved in the game.

Results

A complete evaluation was conducted at one site (a construction firm). The results are as follows.

- Estimated kwh savings per player household based on billing analysis of one year before game and one year after the start of the game: 400 kwh/household annually = 6% median usage savings annually.

- Of 330 employees, 220 (67%) participated in the game. Participation comprised taking one or more of the actions that had been rolled out to-date and reporting it at the end of the week. [Note: this system had been changed to daily reporting in more recent/current games.]

- About half of the players (47%) did so at least once per month, while more than a quarter (29%) played almost every week. In addition, a substantial share of players (more than 40%) reported in a post-game survey that they took actions related to the game that they did not claim and for which Cool Choices had no record.

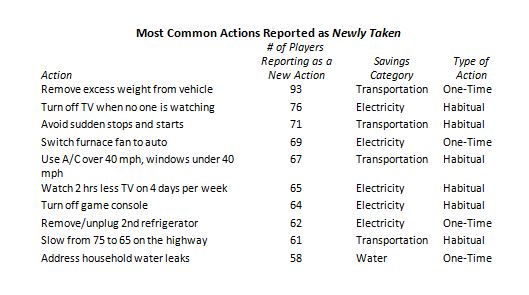

- Players reported a total of nearly 3,500 sustainable actions. Of these actions, 52% were reported by players to be new efforts taken as part of the game.

- In the post-game survey, players reported higher levels of activity to save energy in the home, water in the home, and gasoline two months after the game ended than before it began. Players rated their pre-game activity similarly across saving energy (2.8 on a 5-point scale), saving water (2.7) and reducing gasoline use (2.7). Self-reported increases in these scores averaged 1.1 for saving energy, 0.9 for saving water, and 0.8 for reducing gasoline use. Those who played the game most often reported both slightly higher pre-game levels of activity (generally 0.3 points higher than infrequent players) and modestly higher increases in their self-reported scores (greater average increases by 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 points for home energy, home water, and gasoline, respectively).

- Persistence, measured one year after the game, was high with few actions reverting to the pre-game condition (both one-time actions and habitual actions).

- 100% for replacing 85 percent of incandescent light bulbs with CFLs o 100% for air sealing and insulating to recommended levels

- 100% for switching / keeping the furnace fan setting to / at automatic rather than continuous

- 80-99% for removing or unplugging a second refrigerator

- 60-79% for turning off game consoles when not in use

- The average gasoline savings per player was 76 gallons/year with considerable variation.

- 23% of players reported no new actions related to gasoline / transportation

- 22% reported new transportation actions projected to save 1 to 50 gallons of gasoline per year

- 19% reported new transportation actions projected to save 51 to 100 gallons of gasoline per year o 24% reported new transportation actions projected to save 101 to 200 gallons of gasoline per year

- 11% reported new transportation actions projected to save more than 200 gallons of gasoline annually

- The estimated carbon emissions avoided per player was 5,780 lbs/annually.

- 15% avoided less than 1,000 lbs/annually through new actions

- 13% avoided 1,001 – 2,500 lbs/annually through new actions

- 18% avoided 2,501 – 5,000 lbs/annually through new actions

- 19% avoided 5,001 – 7,500 lbs/annually through new actions

- 15% avoided 7,501 – 10,000 lbs/annually through new actions

- 20% avoided over 10,000 lbs/annually through new actions

- In the post-game survey, respondents reported that they had regular conversations about sustainability during the game—both at home and at work. In fact, 60% of players said that they had such conversations at least weekly.

- In the post-game survey respondents also reported learning from the game.

- 86% of players and 20% of non-players indicated that they were now more aware of opportunities to save energy.

- 88% of players and 7% of non-game players learned something new from the iChoose cards.

Because this was the first pilot application of the game, overall cost effectiveness was not calculated but it will be calculated in subsequent partnerships under this model.

As of May 2013 Cool Choices had completed four sustainability pilot games with partners in commercial construction, health care, law and a game in six U.S. primary-level schools in one region. It ran one additional pilot student/staff transportation engagement game with partners at a U.S. high school. Result estimates below reflect only the four employee/school engagement games and incorporate action savings adjustment estimates based on independent evaluation findings.

Results Through May 2013:

- Total Number of Players Taking At Least One Action Across Four Games: 900

- New Actions: 41,700 total (10,700 one-time and recurring activities)

- Estimated Financial Savings from Individual Actions: $197,600 annually

- Total Estimated Annual Savings

- Electricity: 490,800 kWh

- Water: 1,278,100 gallons

- Gasoline: 35,400 gallons

- Natural Gas: 16,500 therms

- Total CO2 Avoided: 2.3 million pounds

Contacts

Kathy Kuntz

kkuntz@coolchoicesnetwork.org

(608) 443-4271

Notes

There are three main innovations here.

- Cool Choices leverages workplace/school infrastructures to influence what employees/students do in their personal lives as well as at work/school. Utilizing workplaces/schools – rather than neighborhoods – reflects recognition that most of us spend a good deal of time with our co-workers/classmates and that they are influential peers in our lives. Staff knew corporate/school leaders would benefit from a bottom-up employee/student commitment to sustainability.

- Gamification made environmentally sustainable actions more immediate, more compelling and more accessible than other approaches. Further, the game made sustainability visible, helping employees/students realize that it was, indeed, a shared value. The game also was a very effective way to leverage social norms; our post-game research suggests that social interactions within the game (e.g., talking with family or co-workers) is strongly correlated to both the frequency of play and the persistence of habits taken up during the game.

- The approach was low-cost and easy to scale up.

One of the surprising findings in the post-game survey was that more than half of the players said they played the game for “lifestyle benefits”. While Cool Choices promoted a variety of actions that might be tied to higher quality of life (e.g., turning off the television or driving less aggressively), we did not anticipate the way this would resonate with players. As the game evolved a group of players consistently shared stories about the game’s positive impact on their families—lower stress levels, more time talking to each other, etc. We are enormously excited about the potential that people might connect environmental sustainability to quality of life issues.

Finally, here are a few comments from Miron employees regarding the game:

- “We are spending less time watching tv…spending a lot more quality time together…”

- “I’ve started slowing down and I’ve already seen my gas mileage go up.”

- “I am finding there’s a lot of things that tie-over really well between sustainability and wellness.”

- “The game is important, but the bigger message that I am getting from this is that it’s about my life and how I can be more sustainable…I’m grateful for the game in opening my eyes.”

- “This week I successfully combined errands several times. The highlight was only using the car once on the weekend. I combined weekly trips into one on Saturday going to the bank, grocery store, and another store to pick up misc. things and the gas station. I then parked the car in the garage and left it in there the rest of the weekend. I used my bike the rest of the weekend when I needed to go somewhere.”

- “Avoid sudden starts and stops - I have been conscious of this since the transportation month began. Between this and the other changes I have made, my gas mileage has improved by 1-2 MPG.”

- “I used to think I was saving time by speeding up and stopping quickly. I no longer "jack rabbit" drive and have not noticed a difference in how long it takes me to get places.”

- “I started Meatless Mondays at my house because it's easy to remember not to eat meat that day. My husband is a meat lover and I started this for health reasons. It's good to know it's also a sustainable action.”

- “I removed extra tools and items from my car which was about 200 pounds. I did see my change in my fuel efficiency.”

- “Before I made any adjustments to my Toyota Corolla, I checked my gas mileage and was getting an average of 28 mpg. After setting the correct tire pressure, taking out extra weight, blankets, umbrellas, etc., put in clean air filter, changed the oil, and changed my driving habits from always driving 7-8 miles over the speed limit to the actual speed limit, we increased our mpg by 5 mpg.”

Written in 2004 by Kathy Kuntz and Jay Kassirer.

Search the Case Studies