Climate Matters Program for TV Weathercasters

Climate Matters trains and supports American TV weathercasters to report on the local impacts of climate change while reflecting current scientific knowledge and concerns. The program provides participating newscasters with weekly story packages with local data and broadcast-quality graphics that visualize the data. Because of an overt conflict in the meteorology community about opposing views of climate change, the program engaged a conflict mediator who worked with small groups of opinion-leading weathercasters to surface and work through the entrenched conflicts. As climate reporting became increasingly normative, the program ensured that everyone in the weathercasting community knew the behaviors were gaining in popularity. As of 31 October 2020, there were 968 participating weathercasters in 483 local TV stations, in 92% of all US media markets and 99 of the top 100 media markets. Viewers exposed to their climate education became more likely to understand that climate change is already a 'here, now, us' problem. Designated a Landmark case study in 2021.

Background

Note: To minimize site maintenance costs, all case studies on this site are written in the past tense, even if they are ongoing as is the case with this particular program.

In 2007, Ed Maibach and Connie Roser-Renouf came to George Mason University to create Mason’s Center for Climate Change Communication. The Center’s mission is to develop and apply social science insights to help society make informed decisions that will stabilize the earth’s life-sustaining climate and prevent further harm from climate change.

At that time, the petroleum industry had been funding climate change-denying organizations to spread disinformation and the United States had a relatively high number of climate change deniers, relative to other countries. Most Americans perceived the threat as distant—in time, space, and species—and not personally relevant, and only a minority saw climate change as a high-priority concern. This hampered making progress at both the individual and societal levels.

In 2009, with funding from the National Science Foundation (and eventually other philanthropic foundations), Ed Maibach and his colleagues from George Mason University and Climate Central began exploring and developing the potential of TV weathercasters as a community of practice of local climate educators.

America’s approximately 2,200 weathercasters are well positioned to increase community understanding of climate change as a locally relevant problem. They are a trusted source of information about climate change, they have considerable and sustained access to the public, and they are highly trained and experienced science communicators who generally see themselves working in the public’s interest (public safety). In addition, they are a cohesive occupational community of practice: they do the same job; share the same tools and practices; have a shared set of stories, linguistic shortcuts and jargon related to their work; are represented by a professional association; and have a strong shared sense of identity.

Getting Informed

The planning team conducted a survey in 2010 that revealed that U.S. TV weathercasters held a startlingly wide range of views about climate change and were somewhat less accepting of human-caused climate change than was the American population. Less than half of them accepted current scientific knowledge on climate change. Within that minority, nearly all expressed an interest in educating their viewers about the local implications of climate change, but few of them did.

The 2010 survey also revealed key barriers to reporting on the local impacts of climate change.

- Lack of time in the newscast

- Lack of time for field reporting

- Uncertainty about climate change

- Lack of news management support

- Lack of access to appropriate visuals/graphics

- Lack of general management or owner support

- Lack of sufficient knowledge in the subject

- Lack of access to trusted scientific information.

The team focused its subsequent efforts on reducing these barriers to the extent possible, beginning with reducing the time required for field reporting, producing localized visualizations and graphics, and enhancing access to trusted scientific information.

Through conversations with weathercasters at their professional meetings, the planning team also took steps to understand the related benefits that are important to weathercasters and their managers. They found that peer recognition (e.g. awards), news media attention (e.g. positive news stories), audience praise, and ultimately professional advancement are highly valued benefits. The team used every means possible to deliver these benefits to participants in Climate Matters program.

Delivering the Program

The Climate Matters team was expanded to ensure representation from climate scientists (who best understood the facts to be shared with weathercasters and their viewers), social scientists (who best understood how people process risk information), and communication professionals (who best understood how to make the information simple and feasible for use, on-air and elsewhere).

Feasibility and Pilot Testing

To test the feasibility and impact of supporting interested TV weathercasters, the team partnered with Jim Gandy, the Chief Meteorologist at the CBS news station in Columbia, South Carolina (WLTX). While a number of weathercasters had volunteered, Gandy was selected for several reasons: he was an influential (i.e., opinion-leading) member of the weathercaster community; his news director and general manager were supportive of his involvement in the project; and his station's viewers resided in a politically conservative community—meaning they were a difficult audience to interest in climate change education (as compared to viewers in a politically liberal media market). The team’s goal was to develop an approach that would successfully support weathercasters in any US media market, and it decided to develop and test the approach in a challenging media market. (Norm Appeals)

In winter/spring 2010, the team worked closely with Gandy to identify 12 story topics that were relevant to his viewers—based on the climate impacts that were already manifest in Columbia—and that were likely to be timely at some point over the next year (based on anticipated weather conditions) so that the stories would have a weather-related 'news hook.' (Building Motivation, Engagement and Habits Over Time; Vivid, Personalized, Credible, Empowering Communication)

A decade later (2021) the program continued to focus on locally-relevant story topics and data. Picture source: Climate Central website 05/09/2021.

Each story package included local data showing how weather and related conditions had been changing in Columbia over the past 50–100 years and/or how they were projected to change over the next 50–100 years, one or more broadcast-quality graphics that visualized the data, and a set of facts that Gandy could use in real time to produce a story when the weather conditions were relevant. In summer 2010, and over the next 12 months, Gandy aired 13 Climate Matters stories during his weather segments—each averaging approximately 2 min. The impact evaluation of the year-long pilot-test demonstrated that, compared to viewers of other stations, WLTX viewers became more certain of the reality of climate change, more likely to see it as harmful, and more concerned about it.

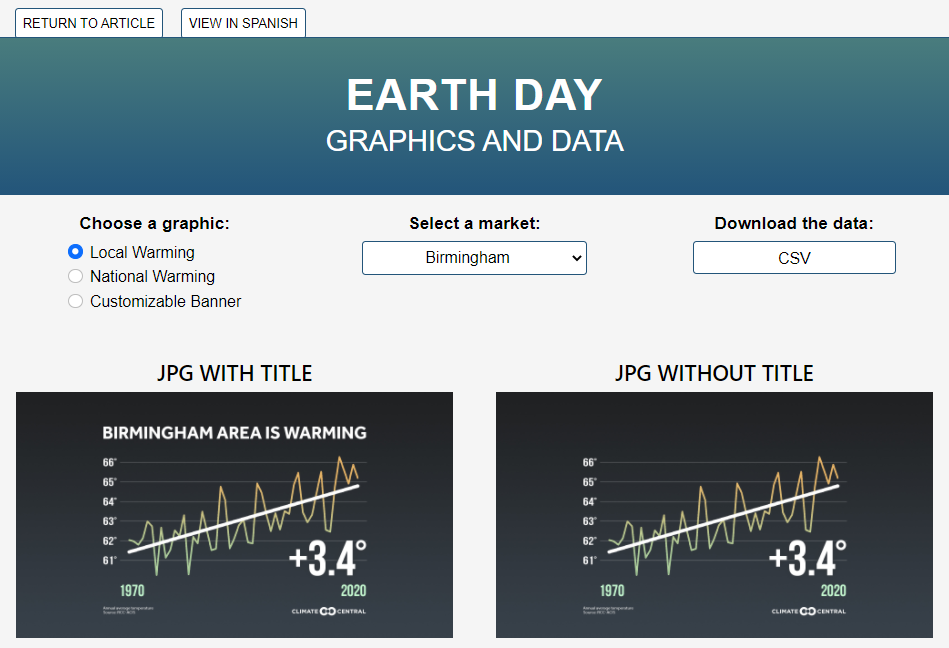

By 2021, site users could generate their own locally-relevant "packages" of graphs and data. Image source: Climate Central website 05/09/2021.

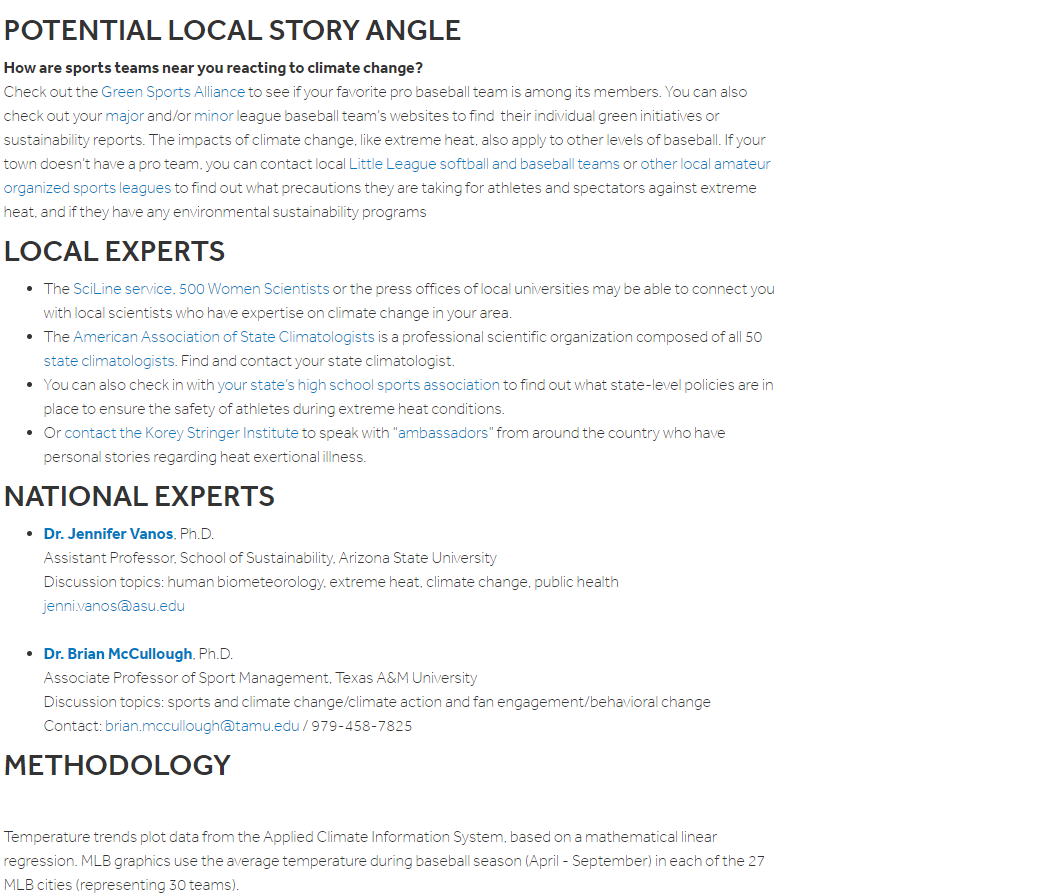

Each "package" included tips for local story angles, and a list of relevant local and national experts. Image source: Climate Central website 05/09/2021.

In addition, the program delivered the key benefits important to weathercasters and their managers (peer recognition, news media attention, audience praise, leading to professional advancement). For example, the team successfully nominated Jim Gandy for the American Meteorological Society’s (AMS) award for excellence in broadcast meteorology, and successfully pitched stories about Jim Gandy to high-profile media outlets including NPR Morning Edition, Columbia Journalism Review, Forbes, and Rolling Stone. (Building Motivation, Engagement and Habits Over Time; Vivid, Personalized, Credible, Empowering Communication)

The next step in the scale-up process was to see if the team could sustain the model while supporting multiple weathercasters in multiple media markets. To that end, in 2012 it invited ten additional opinion-leading weathercasters from a diverse set of media markets nationwide to participate in Climate Matters—with the goal of delivering each of them a story package, localized when possible, every week. Ultimately, it was influencers like these opinion-leading weathercasters who created a new norm in their community of practice.

Scaling Up and Resolving Conflicts

Early in 2013, the team invited all 47 weathercasters in Virginia to participate in the program; 20 accepted the invitation (a 42% participation rate—a strong show of interest. Later that year, the team quietly began enrolling any weathercaster who requested permission to participate, regardless of their location—which necessitated customizing materials for a rapidly expanding set of media markets nationwide. Concurrently, it began offering Climate Matters materials in Spanish as well as English. During this period, the American Meteorology Society (AMS), NASA and NOAA—organizations whose climate information is highly trusted by most TV weathercasters—joined the project to help scale it up nationwide.

As more and more weathercasters joined the program, it became easier for others to join as well. The early adopters modelled how to implement the new behaviors and fostered a stronger sense of self-efficacy in the later adopters that they too could benefit from adopting these behaviors. Further, as climate reporting became increasingly normative, the program made every effort to ensure that everyone in the weathercasting community knew the behaviors were gaining in popularity; this information exerted a subtle but powerful influence that encouraged others in the community to consider and try the behavior. (Norm Appeals)

For example, the team routinely gave presentations at the annual meetings of the AMS and National Weather Association (NWA). Each of these presentations included evidence of positive audience’s reactions to Climate Matters reporting, and featured testimonials by weathercasters who were personally experiencing positive professional outcomes as a result of their climate reporting.(Group Feedback)

.png)

The program also highlighted members' local climate-change-related stories on the Climate Central website. Image source: Climate Central website 05/09/2021.

Because of the overt conflict in the meteorology community about opposing views of climate change, the team engaged the services of a conflict mediator who worked with several small groups of opinion-leading weathercasters to surface and work through the entrenched conflicts about climate change in the community of practice. Starting with dinner and going well into the evening at AMS and NWA annual meetings in 2012, these professionally moderated 3- to 4-hour dialogues with approximately 18 weathercasters each proved to be transformative. The moderator facilitated the respectful airing of grievances, role playing the positions of “the other”, and other standard conflict analysis and resolution techniques. By the end of both sessions, the understanding of “the other’s” position was visibly heightened, and the sense of grievance on both sides visibly reduced. Because the participants were specifically selected to be opinion-leaders in their professional community, the intent was any rapprochement experienced by participants during the dialogues would eventually be spread to others in the weathercaster community. (Overcoming Specific Barriers)

By the end of 2013, over 100 weathercasters were participating in the program, and the number of participating weathercasters continued to grow rapidly. As of April 15, 2021, there were 996 participating weathercasters (56 broadcasting in Spanish), working in 476 local TV stations (and five national networks), in 92% of all US media markets and 99 of the top 100 media markets.

In 2014, participating weathercasters aired 69 Climate Matters stories; in 2019 they aired 3,535 stories (a 50-fold increase over 6 years.)

Educating and Training Interested Weathercasters

Each year since 2013, Climate Matters presented conference papers (1–2-hour conference sessions) at the AMS annual broadcast meeting and the National Weather Association (NWA) annual meeting, both to educate weathercasters and raise their awareness of the program. Starting in 2014, it also hosted 22 intensive, mostly daylong climate reporting workshops, often in association with the AMS and NWA annual meetings, and 6–10 hour long webinars each year. Video recordings of these webinars, and all of the Climate Matters program materials produced to date, organized by topic and media market, can be seen and downloaded from the Climate Matters online media library: https://medialibrary.climatecentral.org/. (Building Motivation, Engagement and Habits Over Time; Overcoming Specific Barriers)

Adding in Newsrooms

In 2018, With Climate Central, Climate Communication, NOAA and NASA, the Centre launched Climate Matters in the Newsroom. Climate Matters in the Newsroom provides journalists with climate reporting training and a range of localized climate change reporting resources, “because climate change isn’t just a weather story.”

Overcoming Specific Barriers

The following table summarizes the main barriers that discouraged participants from doing the desired behavior(s) and how those barriers were reduced.

|

Barrier |

How it was addressed

|

|

Lack of time in the newscast |

· Demonstrated with participating weathercasters that the stories could be told in two minutes or less. |

|

Lack of time for field reporting |

· Provided newscasters with story packages for topics that were relevant to their particular viewers—based on the climate impacts that were already manifest in their particular regions—and that were likely to be timely at some point over the next year. Each story package included local data and one or more broadcast-quality graphics that visualized the data. |

|

Uncertainty about climate change. Overt conflict in the meteorology community about opposing views of climate change |

· Used surveys to demonstrate the increasing consensus about climate change among scientists, weathercasters and the general public. · Engaged the services of a conflict mediator who worked with several small groups of opinion-leading weathercasters to surface and work through the entrenched conflicts about climate change in the community of practice. |

|

Lack of access to appropriate visuals/graphics |

· Each story package included local data and one or more broadcast-quality graphics that visualized the data. |

|

Lack of news management support |

· The Center’s surveys collected information on weathercaster engagement. As climate reporting became increasingly normative, the program made every effort to ensure that everyone in the weathercasting community knew the behaviors were gaining in popularity. |

|

Lack of general management or owner support |

· As above |

|

Lack of sufficient knowledge in the subject |

· Each story package included a set of facts and local data showing how weather and related conditions had been changing over the past 50–100 years and/or how they were projected to change over the next 50–100 years. · Educated and trained interested weathercasters through workshops, conference presentations and webinars. |

|

Lack of access to trusted scientific information |

· As above · Provided contact information and online resources for those wanting more detail. |

Financing the Program

This program was started with funding from the National Science Foundation. Over time, other philanthropic foundations have also contributed to the program.

Measuring Achievements

Impacts on the weathercaster community were measured using the following indicators.

- Number of weather stories about local climate change impact

- Self-reported beliefs about climate change, its causes, the extent of local impacts, weathercasters’ interest in reporting on these issues, and their understanding of their viewers interest. This was gauged using periodic surveys (2010, 2011, 2015, 2016, 2017). The first two surveys were conducted with AMS and National Weather Association (NWA) broadcast members (2010: n = 571; 2011: n = 433; response rate = 33%). Starting in 2016, the Center identified additional American professionals working in broadcast meteorology. The surveys were then sent to over 2,000 weathercasters, with response rates between 22% and 32%.

Impacts on the general public were measured through two studies.

- An internet-based randomized controlled experiment asked local TV news viewers (n = 1,200) from two American cities (Chicago and Miami) to watch either three localized climate reports or three standard weather reports featuring a prominent TV weathercaster from their city; each of the videos was between 1 and 2 min in duration. Participants’ understanding of climate change as real, human-caused, and locally relevant was assessed with a battery of questions after watching the set of three videos.

- A second study analyzed three sets of data in a multilevel model.

- Individual-level (i.e., survey participant-level) factors, including public understanding, were tracked using data from the Climate Change in the American Mind (CCAM) polling project (n= 23,635; 20 waves of the survey.) CCAM has conducted a nationally representative survey of American public opinion about climate change biannually since 2010.

- Time-varying factors (level 2) were tracked using data on when and how frequently Climate Matters stories were aired in each U.S. media market.

- Media market-level factors were tracked using data on the demographic, economic, and climatic conditions in each media market.

Feedback

The Center’s surveys collected information on weathercaster engagement. As climate reporting became increasingly normative, the program made every effort to ensure that everyone in the weathercasting community knew the behaviors were gaining in popularity.

Results

Impacts on Individual Weathercasters

The strongest predictor of a TV weathercaster reporting at least one climate story on air in the prior 12 months was participation in the Climate Matters program.

In 2010, almost none of the weathercasters aired stories about the local impacts of climate change. In contrast, by 2019 each participating weathercaster aired on average 3.5 Climate Matters stories per year.

Participating meteorologists incorporated the program materials in the following ways.

- Put them in their on-air weather segments (most typical use)

- Used them in longer-format on-air news stories outside of the weather segment

- Posted them to social media with comments

- Used them in print reporting on their station or personal blog

- Included them in their in-person public presentations at schools and community events

Impacts on the Weathercaster Community

- As of April 15, 2021, there were 996 participating weathercasters (56 broadcasting in Spanish), working in 476 local TV stations (and five national networks), in 92% of all US media markets and 99 of the top 100 media markets.

- In 2014, participating weathercasters aired 69 Climate Matters stories; in 2019 they aired 3535 stories—more than a 50-fold increase over 6 years.

- One study showed that the program’s conflict mediation process was helpful in moving the community beyond conflict and toward cooperation on the issue of climate communication). Analysis of the transcripts of the sessions, and participant feedback provided after the sessions, strongly suggested increased understanding of the positions of the “the other,” and reduced levels of grievance. Perhaps more importantly, anecdotal reports from many weathercasters indicated greatly reduced levels of conflict about this issue in the weathercaster community over the ensuing few years.

- Concurrent with the growth of the Climate Matters program, there was a dramatic shift in how members of the broadcast meteorology community themselves viewed climate change, such that their views became much more closely aligned with those of climate scientists. The Climate Matters 2010 survey found that only 31% of TV weathercasters were convinced that global warming is caused primarily by human activities and an earlier survey had found that only 22% agreed that “the theory of global warming is accepted by most atmospheric scientists”. In contrast, the 2016 and 2017 surveys showed that more than 90% of weathercasters agreed that climate change is happening, and 80% attributed it to human causes.

Impacts on the General Public

- Two recent impact evaluations have shown that both locally and nationally, viewers exposed to Climate Matters stories become more likely to understand that climate change is a 'here, now, us' problem.

- In one study, compared to participants who watched other weather reports, those who watched Climate Matters climate reports became significantly more likely to 1) understand that climate change is happening, is human-caused, and is causing harm in their community; 2) feel that climate change is personally relevant and express greater concern about it; and 3) feel that they understand how climate change works and express greater interest in learning more about it.

Contacts

Edward Maibach

Professor and Director

George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

emaibach@gmu.edu

Notes

- What is most adaptable about this program is its approach of identifying, training and supporting an influential community of practice. This approach could be applied to a wide range of behaviors influenced by this and other communities of practice.

- According to the program team, taking a community of practice approach with TV weathercasters was the essence of the success of the Climate Matters program. This is important because many professional communities need to update their professional practices to deal with the implications of the world’s changing climate —for example doctors, fire fighters, and HVAC installers. The community of practice approach may be an efficient and effective way to work with a broad range of professional communities to update their practices.

- The replicability of this approach to other locations has been demonstrated by its rapid adoption across United States. In addition, Professor David Holmes, Director of the Climate Change Communication Research Hub at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) has successfully replicated and extended key elements of Climate Matters in Australia.

Authors and Landmark Designation

This case study was written by Jay Kassirer and Ed Maibach in May, 2021.

The program described in this case study was designated in 2021. Designation as a Landmark (best practice) case study through our peer selection process recognizes programs and social marketing approaches considered to be among the most successful in the world. They are nominated both by our peer-selection panels and by Tools of Change staff, and are then scored by the selection panels based on impact, innovation, replicability and adaptability. The panel that designated this program consisted of:

- Kathy Kuntz, Dane County Office of Energy & Climate Change

- Doug McKenzie-Mohr, McKenzie-Mohr Associates

- Britta Ng, City of Coquitlam

- Susan Schneider

- Brooke Tully

Search the Case Studies