The Healthy Penis Campaign

The Healthy Penis was a humor-based campaign that increased syphilis testing and awareness among gay and bisexual men in San Francisco.

Background

San Francisco experienced a sharp rise in early syphilis between 1999 and 2002, with the number of cases rising from 44 to 494 per year. Most of the syphilis cases were among men who identified as gay or bisexual (88%), were white (60%), and were infected with HIV (61%).

In June 2002, the San Francisco Department of Public Health's (SFDPH) STD Prevention and Control Services launched a social marketing campaign, called the Healthy Penis, designed to increase syphilis testing and awareness among gay and bisexual men

Setting Objectives

Based on the characteristics of the target audience, and with input from the community partners group, the SFDPH determined that the primary campaign message should be “get tested,” with the main objective of changing community norms around syphilis testing.

Secondary objectives were to increase awareness about the syphilis epidemic in gay and bisexual men and to increase knowledge about syphilis in general (symptoms, routes of transmission, the link between syphilis and HIV transmission, etc.).

Ultimately, the campaign sought to have the target audience undergo routine screening (every 3-6 months), which would help the health department identify new cases and decrease the duration of infectivity.

Getting Informed

The campaign was initially conceived and developed by Better World Advertising, a gay-owned media company with a history of successful HIV prevention advertising, in collaboration with staff from the SFDPH.

All campaign materials were reviewed by focus groups of gay men and key community leaders; draft materials were also circulated on an Internet list-serve of gay men in San Francisco.

Focus groups expressed a need for basic facts about syphilis and information on testing and other services; however, participants did not want the campaign to be judgmental or discuss sexual risk behaviour. They said that scare tactics would be tuned out, and that didactic messages could be perceived as "preachy."

Since the community was already inundated with HIV prevention messages, the campaign needed to stand out. The chosen approach was specifically designed to be sex-positive, bold, and humorous; provocative elements (e.g., penis costumes and squeezie toys) were intended to raise awareness and generate secondary waves of discussion.

All feedback (from focus groups and the list-serve) was reviewed by the development team, and the health department’s executive staff approved the final materials.

Targeting the audience

Epidemiological data determined that the target audience should be gay and bisexual men who lived in San Francisco. The campaign was promoted in neighborhoods where the greatest concentration of gay or bisexual men lived and where there were businesses that catered to this population.

Key messages included:

- Syphilis is on the rise among gay and bisexual men in San Francisco.

- If you are a sexually active gay or bisexual man in San Francisco, get tested for syphilis every 3-6 months.

- Methamphetamine use increases your risk of acquiring syphilis.

Delivering the Program

The first phase of the Healthy Penis campaign was launched during the annual San Francisco Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Parade in late June 2002 and continued through December 2005. A second phase followed, after a related social marketing campaign ended.

Phase I

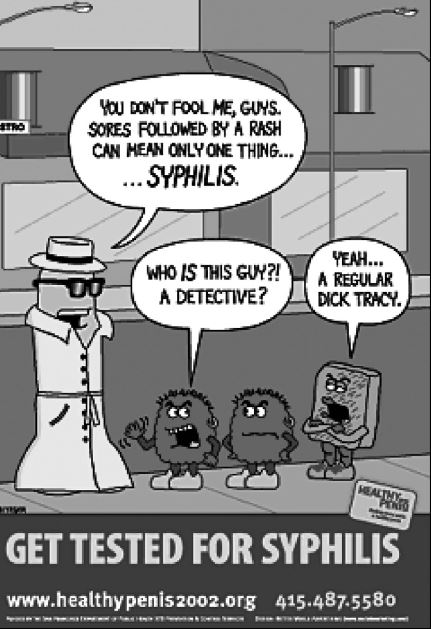

The campaign incorporated the use of humorous cartoon strips that featured characters like the Healthy Penis and Phil the Sore. (Vivid, personalized communications) These characters helped spread messages about:

- Syphilis testing

- The rise of syphilis among gay and bisexual men

- Information on syphilis transmission, symptoms and prevention, and

- The connection between syphilis and HIV.

The cartoon strips were initially published semi-monthly in a popular gay Bay Area publication. After publication, poster-size reproductions were posted on the streets, bus shelters and bus advertising, in bars and commercial sex venues, and on banner advertisements on one of the most popular Internet sites for meeting sex partners among gay men. (Mass media) Messages were targeted by neighborhood and in venues where gay men frequented, during hours when the most number of men could be reached.

Topics addressed in the cartoons initially emphasized all of the messages described above; after a year and a half, the campaign focused on the “get tested” message.

In addition to messages contained within the cartoon strips, brief text boxes were displayed on the bottom of the cartoon images describing modes of syphilis transmission (skin-to-skin contact, oral, anal and vaginal sex), symptoms (painless sore and/or rash), and explaining that syphilis is curable. These text boxes were displayed on cartoons from June 2002 to October 2003 with decreasing frequency.

Promotional items were handed out at events (Incentives) and included:

- Palm cards

- Magnets, and

- Photos taken with one of three 7' tall Healthy Penis costume characters, which were then posted on the Healthy Penis website and on social networking websites (Facebook, MySpace and Twitter). (Mass Media)

.JPG)

Phase I of the Healthy Penis campaign ended in San Francisco in late 2005. The campaign was subsequently implemented in other cities that had increasing syphilis rates among gay and bisexual men (Cleveland, OH, San Jose, CA, Seattle, WA, and Winnipeg, MB).

Phase II

In mid-2007, community leaders in San Francisco felt that the Healthy Penis campaign was “getting old,” so a new social marketing campaign called “Dogs are Talking” was introduced with the primary objective to increase syphilis testing among gay and bisexual men.

This campaign was more limited in budget and scope than the Healthy Penis campaign. It was designed in conjunction with another local social marketing firm, Promotions West, along with input from community members, and was meant to appeal to the large number of gay and bisexual dog owners in San Francisco. However, an evaluation found that awareness of this campaign was low and organizers ended the program in late 2008.

Although the incidence of early syphilis in San Francisco in 2005 was lower than in the previous three years, and declines continued through 2007, in 2008 early syphilis incidence spiked to almost 500 cases among gay men and remained high through 2009. Reasons for this increase were unclear, but could have included decreased resources allocated to syphilis prevention and control resulting in early clinic closures, fewer public health field workers, and decreased community engagement, issues which persisted through 2010.

In response, health officials and gay community leaders reintroduced the Healthy Penis campaign in February 2009. The new campaign featured three Healthy Penis characters of different ethnicities, Clark, Byron, and Pedro, along with an updated serial comic strip. (Vivid, personalized communications)

Partnerships

The campaign was created by Better World Advertising and launched in collaboration with the San Francisco Department of Public Health. The campaign was also developed in collaboration with the Los Angeles Department of Health, which opted for a "Stop the Sores" campaign centred on the character "Phil the Sore" rather than the "Healthy Penis," after feedback from its local gay community groups.

Partners also included community testing sites and retail businesses in the Castro area of San Francisco.

Financing the Program

The SFDPH funded the Healthy Penis campaign and its evaluation. Partnering with the Los Angeles Department of Health allowed campaign organizers to lower their start-up costs to $75,000 in 2002. The campaign was continued through the end of 2005 at an additional cost of $295,000. Three-quarters of the campaign's first-year funds were spent on campaign development, with the remaining quarter spent on displaying campaign materials. The costs of evaluating the campaign included data entry and analysis and 13 survey interviewers. These costs totaled approximately $US 11,360. An unpaid intern performed data entry for street-level surveys.

The cost to relaunch Phase II of the campaign was $US 104,130.

Measuring Achievements

The effectiveness of the campaign's first phase was assessed using:

- Clinic testing data

- Clinic survey data

- Street intercept survey data

- Number of hits on the Healthy Penis website, and the number of friends Facebook and MySpace pages, and on Twitter.

The campaign was unable to conduct baseline measurements. Two waves of surveys were conducted using the same survey: Evaluation I (EI) took place six months after the campaign began (December 2002 to February 2003); Evaluation II (EII) took place two and half years after the campaign began (September 2004 to March 2005).

For each survey, men were intercepted at coffee shops, bars, markets, laundromats, sex clubs, a clean and sober community centre, on sidewalks and in other venues located in campaign-targeted neighborhoods.

Respondents were asked about:

- Basic demographic information

- Unaided (e.g., spontaneous mention) and aided (e.g., prompted response) awareness of the Healthy Penis campaign

- Perceived key messages of the campaign: syphilis knowledge (via open-ended questions); sexual practices in the past month; HIV status; and how many times they were tested for syphilis in the past six months.

Comparisons were then made among those aware of the campaign between the first and second sample of respondents. Recent history of syphilis testing was compared with campaign awareness level for each evaluation separately. Analysis included Fisher's Exact (statistical significance) and Cochran-Armitage (trend) tests, and logistic regression.

In EI, 244 interviews were conducted with San Francisco residents and 150 interviews were included in EII. All respondents were men, aged 18-60, who had sex with men and most were white and HIV negative. There were no significant demographic differences between the first and second evaluation participants.

Results

Campaign awareness was high with 80% (EI: 194/244) and 85% (EII: 127/150) of respondents aware of the campaign.

Awareness was similar between the two evaluations: 33% (aided) versus 41% (unaided) mentioned the Healthy Penis campaign when asked to recall recent advertisements or public events about sexual health issues; an additional 47% (EI) versus 44% (EII) recognized the campaign when shown a campaign image. There was no difference in overall campaign awareness, unaided awareness, or aided awareness between the two evaluations.

Of those surveyed, 40.7% of those who saw the campaign agreed that it had influenced them to get tested.

There was a strong positive association between campaign awareness and recent syphilis testing.

After controlling for extraneous variables (i.e., age, HIV status, casual sex partners in the last month), each increase in campaign awareness level during EI (none vs. aided awareness vs. unaided awareness) was associated with a 90% increase in likelihood for having been tested for syphilis in the past six months. The same multivariable model applied to EII respondents found each increase in campaign awareness level to be associated with a 76% increase in likelihood for having been tested for syphilis.

Knowledge of the campaign’s key message (“get tested”) also increased over time with increasing exposure. This effect was sustained for almost three years.

Gay and bisexual men who were aware of the campaign were also more likely to have greater knowledge about syphilis than those unaware.

In both evaluations, HIV-infected respondents showed an increased likelihood of syphilis testing than those who were HIV negative. Overall, reported syphilis testing in the previous six months did not change from the first evaluation to the second evaluation (42% versus 49%).

In 2005, the incidence of early syphilis was lower than in the previous three years, with decreases in cases in gay/bisexual men accounting for the drop. Although campaign evaluations were cross-sectional and causality cannot be determined, it did appear that the Healthy Penis campaign, along with other SFDPH syphilis elimination efforts, may have led to this decrease in syphilis incidence.

Additional indicators:

- 52,345 website hits; 28,316 of those hits were searches to learn about the basics of syphilis

- Approximately 2,348 individuals became friends of one of the characters on the Facebook or MySpace sites.

- Most of those surveyed saw campaign materials on posters and on buses (shelters and in-bus.

Contacts

Jacqueline McCright, MPH

Community STD Services Manager

San Francisco Department of Public Health Jacque.McCright@sfdph.org

T. 415-355-2015

http://www.healthypenis.org/

Notes

Lessons Learned

Invest in campaign development

Campaign organizers believed that spending more on start-up resources on campaign development rather than campaign placement likely led to the high level of campaign awareness and demonstrated that the messages resonated with the target audience.

Partnerships help lower costs

By partnering with another jurisdiction (Los Angeles), campaign organizers lowered their start-up costs and created a Community Partners Group, which helped tailor campaign messages to be most effective.

Well-planned evaluations are critical

Campaign organizers carefully planned their evaluations and evaluation techniques to assess the impact of the campaign. These evaluations helped support a continuation of the campaign (Phase II) in San Francisco, as well as in other U.S. and Canadian cities.

Planned comparisons of pre- and post-campaign syphilis testing rates among gay men might also have provided more compelling evidence of campaign effectiveness (e.g., some community members were reluctant to ascribe increases in syphilis testing to the effect of the campaign).

Community input

The Healthy Penis campaign was developed with input from the affected community and this was seen as a key factor in successfully reaching the target audience and leading to a reduction in syphilis incidence in 2005. By actively participating in the campaign’s development, community leaders provided critical insight, feedback, credibility and balance, and helped create the campaign messages and materials.

Better communication with local authorities

All health department executive staff were aware of the campaign from the start, but not all local authorities felt comfortable with every component of the campaign, despite its impact.

In the future, communication with and participation of an expanded group of political and community stakeholders would be helpful.

Note: This case study was written in 2014 by Jay Kassirer and Heather Bowen Ray, with funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada.